China’s party-state consists of multiple nested hierarchies of bureaucrats and officials accountable to a common leadership, yet it also gives substantial autonomy to lower levels of government in pursuing various objectives. By some fiscal measures, China is the most decentralized country in the world. As such, China’s particular flavor of “quasi-federal” control, as well as its integration of party and state, will heavily influence and constrain options for controlling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the economy. This paper describes the evolution of decentralization over the reform period that began in China in 1978, different theories of institutional change in China, and how the empirical and theoretical literatures help us understand the development of institutions for governing GHG-emitting activities.

Climate policy merits this extended look at the subnational Chinese state for several reasons. First, large institutional transformations are required to align the incentives of government bureaucracies with the new goal of reducing GHGs across a wide range of established government functions. Second, the local political economy embedded in government institutions ensures that this task is significantly more complicated than prescribing a single set of ideal institutions (e.g., based on international best practices). There will likely be extended periods of geographic variation in policies and institutions. Third, effective policy prescriptions will thus require creative use of centralization where local interests diverge substantially from national objectives, but must also align with and exploit local government authorities to advance rapid reforms in other areas.

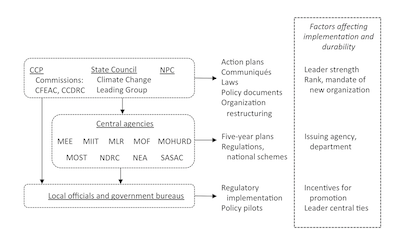

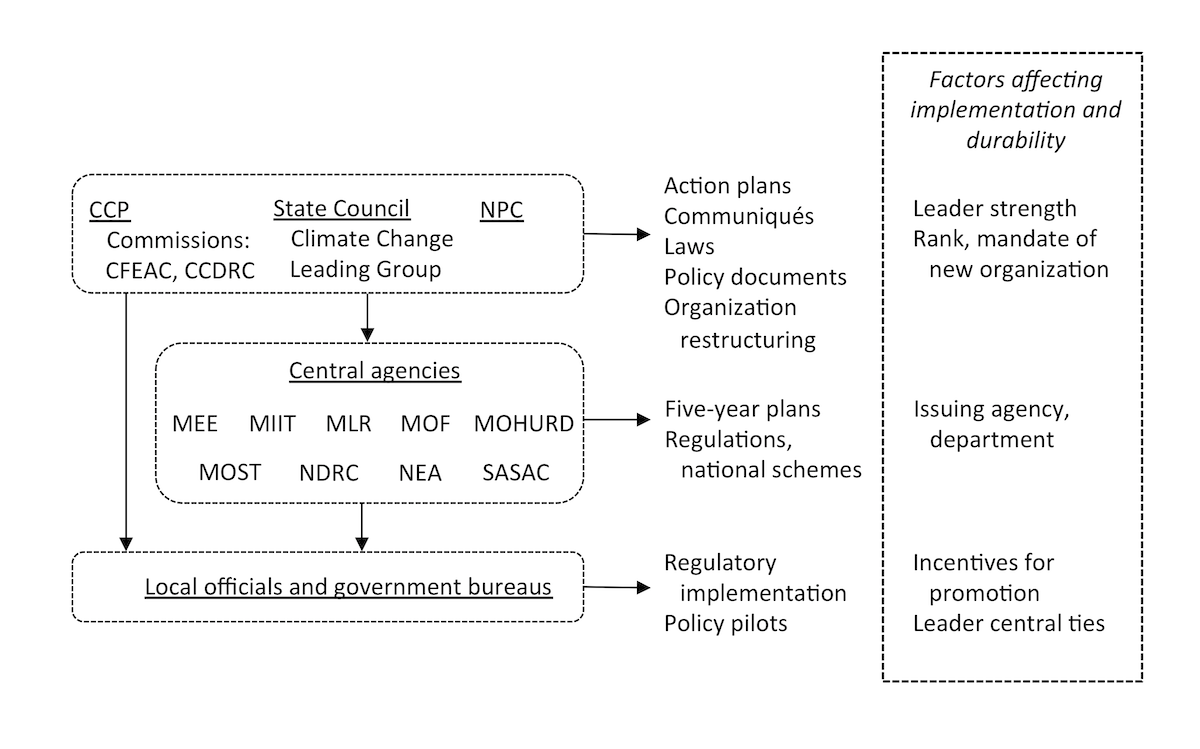

In terms of institutional functions, China’s central agencies have a great deal of power over economic planning, tax policy, some pricing, and standard-setting. Meanwhile, local governments control much permitting, other aspects of pricing, portions of production, and land policy. Since 2007, these functions have increasingly reflected climate change concerns, though the priority given to reducing GHG emissions is by no means uniform across central and local government institutions. Additionally, there remain crucial gaps in the overall institutional framework that would elevate the importance of climate change. Central enforcement of policy implementation generally increases when policies align with other, arguably more salient, policy goals, such as reducing air pollution.

Personnel decisions crucially determine many aspects of implementation: local officials are directed and constrained by superiors via cadre-leadership selection and promotion, administrative mandates, and budgets. Strong relationships—and consonance of interests—between provincial and central authorities and institutions may facilitate policy implementation by provinces. However, such strong ties may also reduce local officials’ flexibility in adapting policies to local conditions—and hence reduce policy effectiveness. On the other hand, if the implementation process primarily reflects local interests, state objectives may not be achieved.

These findings have implications for the design and implementation of the national carbon market set to start around 2020. The newly-created Ministry of Ecology and Environment is the locus for climate change policy, but its authority within China’s complex institutional framework is still being developed, at both central and local levels. One important component of fully implementing a national carbon market will be to harmonize existing province- and city-level pilot GHG trading programs with the goal of generating efficient prices and eliminating cross-provincial trading barriers. However, this will be complicated by differing local policy designs and industry structures. More fundamentally, the interests of the provinces and municipalities with considerable (though not exclusive) authority over their pilot programs must be aligned with the central priority of advancing the national GHG trading system. Another challenge is the absence of a well-functioning market for electricity—the first sector targeted under the national carbon market. Designers of the national carbon market are therefore developing second-best “rate-based” approaches and “indirect emissions” permit systems. Ultimately, the success of the national carbon market will depend on electricity market reforms, which are being pursued in parallel and have an uncertain end-date.

Figure 2: Organizations, major policy levers, and factors affecting the implementation and durability of climate policy in China

Figure 2: Organizations, major policy levers, and factors affecting the implementation and durability of climate policy in China

With the support of the Harvard Global Institute. In collaboration with Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment, and Economy

Recommended citation:

Davidson, M. (2019). Creating Subnational Climate Institutions in China (Discussion Paper). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Project on Climate Agreements.